This post was written by Carlos Justiniano and first published on the HackerNoon website.

This is a post about hacking — not the kind of hacking that has come to refer to breaking into computer systems (cracking), but rather the positive hacking that seeks to explore, understand, and share. If this form of hacking is new to you then this Wikipedia entry may be insightful.

In this context, hackers are explorers and experimenters. This is seen in such diverse realms as art, computer programming, the maker movement, and biohacking. So why not time?

I first encountered the term Time Hacker when I discovered the Time hackers podcast by @ImJulieTweets. In her podcast, Julie examined productivity tips which allow you to do more with your time.

For me, the subject of time hacking resurfaced while watching actor BD Wong’s portrayal of Whiterose, the transgender leader of the Dark Army in USANetwork’s series Mr. Robot.

In her brief scenes, Whiterose is interrupted by the chime of her watch — a reminder of passing time. Watching Whiterose one gets the sense that she has a keen appreciation and control of time...

Appreciating time

Appreciating time is at the heart of using time to ones benefit. But to truly control our use of time we must first embrace it. So how does one go about embracing time? One way is by changing your relationship to it. To paraphrase a popular saying, you either drive time or time drives you. Are you a victim of time or a manipulator of it? Take a moment to consider what sort of relationship you have with time.

Wait. Back so soon? Well, to be fair, the truth is that most of us don’t think of time that way. One problem many of us suffer from is the illusion that we have unlimited amounts of time at our disposal. Intuitively we know this just isn’t true, but many of us simply don’t behave that way. From a moment to moment perspective we feel as though we have lots of time before our internal clocks cease to tick. Surely, we can spare a few? So a task gets pushed to a later time and we’ll eventually get around to repainting the house or taking that dream vacation.

Along the way, many of us lose track of time.

One reason for this is that most of us tend to appreciate things that are scarce to come by, while things like air and sunlight, go largely unappreciated.

A key to appreciating time is to view it in the context of smaller chunks rather than years, months or even days. This is not to say that you shouldn’t have a roadmap which outlines a longer journey. But rather, that focusing on a singular chunk of time allows us to consider what we’ll accomplish during that time. After all, being present and fully committed to a single activity is how memorable moments are created. You’re far more likely to appreciate time spent this way.

Respecting and appreciating time are the first steps toward reclaiming the time that slips away from you.

. . .

The TimeHacker Method (THM)

THM is an approach for seizing blocks of time in order to do more of what matters. THM offers a different way of seeing time. At its core, the hack is to detach our perception of time from the surface of a distant goal or even a looming deadline — and instead view time in the context of a day. A day filled with a finite collection of singular blocks of time. Our efforts within each time block should be short and highly focused. And it’s ok if you don’t schedule many blocks throughout your day. It’s more important to view them as unique opportunities to become committed, highly focused and determined to accomplish a task. As your appreciation of time grows so will your number of time blocks.

During an individual time block only the task at hand matters. All other distractions are met, quickly cataloged and temporarily discarded. The goal is to provide extreme and mostly undivided attention during that period. Most importantly you avoid thinking about the parent task that the current task is a part of. Not doing so often leads to distractions which include fear, uncertainty, and doubt. And overthinking instead of simply doing. By limiting scope and creating context, we increase our laser focus. To paraphrase Bruce Lee: be like the laser my friend.

THM consists of four phases:

- Phase 1: Determine your average working time.

- Phase 2: Plan how you’ll use that time.

- Phase 3: Do

- Phase 4: Visualize time

We’ll review each phase, but keep in mind that the fourth phase “Visualize time” is the binding element. It’s what will allow you to appreciate and leverage time rather than losing sight of it.

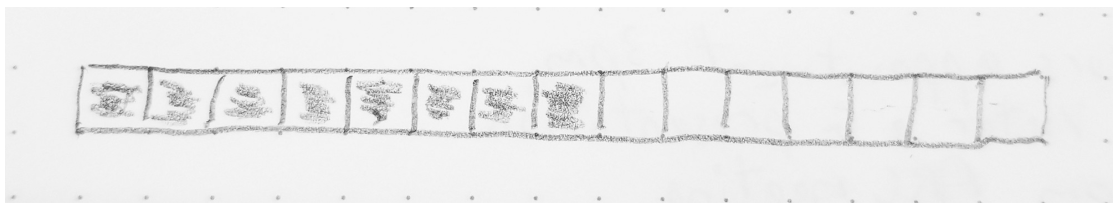

John begins by taking inventory of what he wants to achieve on a given day. He either does this the night before or just before he starts his day. Part of that process is the determination of how much time he’ll devote. John decides that completing a new product prototype is his top priority and that he’s willing to devote six hours to achieving that goal. So he has six one hour segments to work with. Using pencil and paper (or a time hacker clock), John is able to track how many of those hourly segments remain throughout the day.

John then creates a list of sub-tasks, which we’ll call micro-tasks. Each task is ideally do-able within 15 minutes — but some tasks might take several 15 minute time blocks to achieve. John uses 15 minute timed blocks in order to remain focused on a specific tasks. He sets a timer / stopwatch to know when each block has expired. At the end of each time block, John reassesses whether he’s completed the micro-task or whether he needs another block. John decides he needs another block but alas nature calls and he needs a short break. As John resumes another time block he centers himself and attempts to block out distractions. He understands that presence and focus is key to achieving his goal.

Every hour John pauses and considers how many one hour segments remain in his day. This is an opportunity to reassess whether he’s on track and to make any necessary course corrections.

At the end of the day, John takes inventory of what got done and what still remains. He uses a journal to track his progress and to plan the goals and micro-tasks for the next day.

Susan might follow a similar path as John, but might instead have only three hours to devote and three goals to complete.

. . .

Let’s take a closer look at each phase.

Phase 1: Determine your average working time

We begin by determining the range of daily hours we’re willing to use for productivity.

For me, it’s from 5 am until 8 pm. 15 hours. Essentially the time I wake up until the time I theoretically should call it a day. Naturally, I’m doing all sorts of things during that time range — but the range defines the overall scope of where tasks can be accomplished.

Phase 2: Plan how you’ll use that time

Understand that within a time range every passing second results in less available time. So it’s important to plan how you’ll use your time. Not per minute — instead think in terms of the most important tasks. Tasks that measurably move the needle on the gauge that measures your goals.

You should only have a handful of daily tasks, ideally only three or so. Those are the tasks that matter and the ones you’ll visualize within the context of your daily available time.

Next, create a list of micro-tasks which will bring you closer to completing your three goals. The key here is to divide a larger task into smaller, more manageable chunks. Each micro-task should be something you can accomplish within 15 minutes of highly focused effort. See the links at the end of this post if you’re interested in why 15 minutes was chosen.

This phase should be done daily in the evening in prep for the next day. However, you might instead prefer to do it in the early morning in prep for the current day. Either way, you’ll take inventory of the micro-tasks you completed and how that affects your overall goals. Use that as an opportunity to course correct and create a new set of tasks.

Phase 3: Do

In Phase three we actually work on assigned micro-tasks. Again, the key here is to engage in highly focused work.

It’s fine if you don’t complete a micro-task in 15 minutes. Simply allocate another 15 minute time block to try again, immediately after — or at a later time.

Make sure to actually use a timer (stopwatch / alarm) during a micro-task — there are thousands of such apps for mobile phones and smart watches. However, for this hack I ended up creating a series of specialized clocks, called, Time Hacker Clocks — they’re freely available as open source projects. More about them later.

Phase 4: Visualize time

You can do this with pen and paper, by simply drawing a bar with as many segments as the number of hours you’ve allotted in your day. You can shade a segment with every passing hour.

The point here is that you don’t need fancy tools to do this. Pencil and paper will do.

As simple as this method seems, it’s likely that we’d simply forget to follow it as we go about our day. This is where an hourly chime is useful. You could set an hourly alert on your watch or mobile device in order to remind yourself to refocus and take inventory of how much time you have remaining for the day. Ideally, this reminder is an opportunity to glance at your time tracker (watch, journal etc…) and take a moment to visualize your remaining time. Ask yourself whether what you’re doing is in line with your goals for the day. It’s ok if it isn’t! The key here is that you’re considering how you’re using your time. This also allows you to consider your goals and whether you’ve created micro-tasks which are achievable and help move you further along.

. . .

So that’s the TimeHacker method. Deceptively simple yet powerful.

. . .

What if I’m in the zone?

You might wonder whether this whole time hacking approach won’t simply interrupt you when you’re in the flow or zone? The answer is — not unless you allow it to. If you’re in a productive flow why interrupt it? Simply stop the timer and keep cranking. However, make sure you’re actually in the zone and not a rabbit hole. If it’s the latter you’re better off coming up for air and refocusing by reassessing, asking better questions and creating new micro-tasks.

It’s important not to think of this as a rigid approach. Like all hacks, this is just a starting point for you to explore, learn and to share.

. . .

Benefits of this approach

A key benefit of this approach is that it focuses on doing what matters most and using simple techniques to stay on track. The approach isn’t focused on helping you do a dozen things, rather it encourages doing less with greater presence, intent and commitment.

The use of timed micro-tasks force us to use intense focus whereby stretching time.

A key aspect of this approach is the use of tools to visualize time — particularly the passing of time.

Getting started

The THM described here is conceptually simple, but it’s harder to do in practice. You’ll find the following tools helpful in getting the most out of this approach.

- Use a paper notebook. Tracking tasks are easier when you write them down and review them over time. If this method appeals to you check out bullet journaling. There is an entire online community devoted to journaling hacks.

- Use an app such as Evernote. It’s a digital notebook that’s always with you. That is if you don’t forget your phone.

- Use a timer. You’ll need a way to keep track of two types of time: 1) The daily time remaining and 2) The time remaining on an individual micro-task. Doing both with one timer is challenging — so you’d need to use a stopwatch and perhaps the printed method I described earlier using a notebook and shading in passing hours. Or you could simply use two timers.

- Phase 4: Visualize time

I actually use a combination of the methods described above. As much as I love digital tools — I’m often reminded that sometimes pencil and paper are still hard to beat.

However, keeping track of time is definitely a task that can be automated and delegated to our digital devices. I set out to tackle this problem by building Time Hacker Clocks. The clock works by using shapes and colored light to indicate how much time remains. The reason for using light is that it’s easier to read colored lights than to mentally read and process text.

Next steps

Review the simple steps above and try them for yourself. This wouldn’t be much of a hack if you weren’t encouraged to experiment with this approach and tune it to meet your needs. If nothing else — this approach is infinitely hackable. Because remember, time hacking isn’t about doing more — it’s about protecting and creating the space-time to do more of what matters.